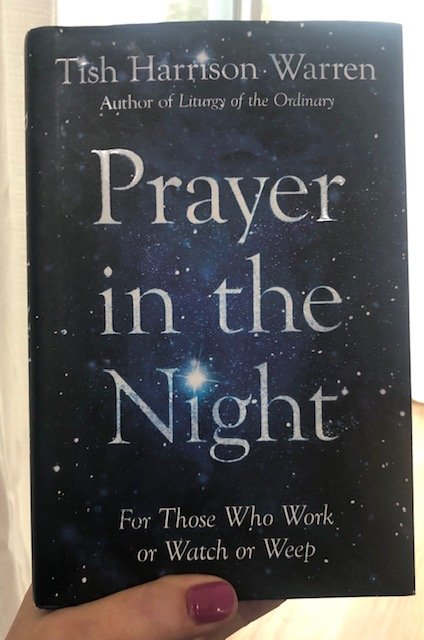

Prayer in the Night | For Those Who Work or Watch or Weep by Tish Harrison-Warren

In the middle of the night, covered in blood in an emergency room, I was praying.

We had lived in Pittsburgh for less than a month. Amid frigid nights and snow that had turned to gray slush, I was miscarrying.

Kind of a shocking beginning. These are the first two sentences of the Prologue of Prayer in the Night by Tish Harrison-Warren. Not what you expect when you open a book titled for a prayer from the Common Book of Prayer. I’ve had a miscarriage myself, plus the fear of another one in my following pregnancy. These sentences immediately brought up the image and feelings I had when I discovered bright red blotches of blood on my underwear, leeching into my clothing. The despair I felt when I found this bleeding at the exact same time—12 weeks—into my pregnancy following the miscarriage was especially vivid. I can imagine what Harrison-Warren felt. In her case, she had multiple miscarriages. The sadness, fear, and hopelessness must have been even more heart-stopping.

Harrison-Warren goes on to describe the experience in the labor room. She yelled to her husband Jonathan, “Compline! I want to pray Compline.” Jonathan explained to the hospital staff that he and his wife are both Anglican priests and they were going to pray now. Harrison-Warren writes:

Over the metronome beat of my heart monitor, we prayed the entire nighttime prayer service. I repeated the words by heart as waves of blood flowed from me with each contraction.

She asks and then answers herself:

Why did I suddenly and desperately want to pray Compline underneath the fluorescent lights of a hospital room?

Because I wanted pray but couldn’t drum up words.

I grew up saying the Lord’s Prayer at church and sometimes in other gatherings, but when I would read about or see people reciting other prayers, it seemed kind of odd to me. In the Barbara Pym novels, sometimes a character comments sardonically on the prayer an English priest decides to recite before an event, thinking they should have picked a different one more relevant to the situation, implying the choice was random and thoughtless. The whole idea of reciting a prayer by heart rather than saying one from the heart struck me as something that wasn’t as meaningful. But what Harrison-Warren says certainly makes sense. Using words from prayers you have learned when you can’t think of words yourself makes a lot of sense. And, as she portrays in this experience of trauma during a miscarriage, very meaningful and heartfelt.

Here’s one paragraph relevant to that:

Faith, I’ve come to believe, is more craft than feeling. And prayer is our chief practice in the craft.

The first thing I think of with the word “craft” is woodcraft. There are many crafts—sewing and needlework, painting, drawing, repairing cars, playing the piano—all things you learn how to do with your hands and practice to perfect. Craft requires practice. In the case of prayers like the Compline as Harrison-Warren talks about it, it might require memorization, which also entails practice. Practice is doing something repeatedly, usually on a schedule. Like the practice of meditation, the practice of exercise, or a devotional practice or religious practice…or prayer practice. As I am studying Ignatian practices I try to pray, meditate, and journal every day. When Harrison-Warren says prayer is the chief practice of faith, it means prayer is how we “get better” at faith, the way we get better at sports or playing piano by practice.

I can relate to struggling to drum up my own words for prayer, as Harrison-Warren says she did during the emergency she describes. It happens to me a lot. Often when I’m asked to pray aloud for a group I struggle with what to say. Or when I pray for someone who is sick, I run out of words after the basic “please help so-and-so to get better.” Since reading this book I have begun to pay closer attention to prayers written by others. Using their words to express my feelings can be wonderful. It’s like when I read books and authors say exactly what I feel with words much better than anything I could have come up with. Those words, those sentences, those gems on the page are one of the reasons I love to read. Why not use the gems of others in my prayers? What a good thing to offer up to God.

You probably think a book about a prayer would be boring but I did not think so at all. There were many of those gems. Here is one regarding vulnerability, a word we often hear these days.

I mean the unchosen vulnerability that we all carry, whether we admit it or not. The term vulnerable comes from a Latin word meaning “to wound.” We are wound-able. We can be hurt and destroyed, in body, mind, and soul. All of us, every last man, woman, and child, bear this kind of vulnerability till our dying day.

Using the word “wound-ability” rather than vulnerability or talking about being hurt seems much more impactful. To imagine an actual wound coming into being because of something I said or did makes a graphic image in my mind. I don’t want my words to cause a wound in someone.

Harrison-Warren has a chapter for each phrase of the Compline prayer.

Keep watch, dear Lord, with those who work, or watch, or weep this night,

and give your angels charge over those who sleep.

Tend the sick, Lord Christ;

give rest to the weary,

bless the dying,

soothe the suffering,

pity the afflicted,

shield the joyous;

and all for your love’s sake. Amen.Book of Common Prayer

In the chapter titled “Keep Watch, Dear Lord: Pain and Presence,” Harrison-Warren tackles the problem of pain, theodicy, the problem of why bad things happen to good people.

If there is no one to keep watch with us, no one we can trust to look out for us in the night, then anything that happens, however good or bad, is sheer chaos, chance, and biological accident. But belief in a transcendant God means we are stuck with the problem of pain…

At the end of the day…the problem of theodicy cannot be answered. As Flannery O’Connor wrote, it is not “a problem to be solved, but a mystery to be endured.”

…The problem of pain can’t be adequately answered because we don’t primarily want an answer. When all is said and done, we don’t want God to simply explain himself, to give an account of how hurricanes or head colds fit into his overall redemptive plan. We want action. We want to see things made right.

Isn’t that the truth? We think of the problem of pain like a math problem or a mystery novel plot we can solve, we can find an answer to. But Harrison-Warren is right—what we really want is for God to make things right. And, as we know, as Harrison-Warren says, this paradox is like a “chord humming in dissonance for thousands of years, only [to be] resolved when God himself sounds the final consonant note…

And I won’t be fully satisfied until God—before whose face our questions die away—sets every last thing right.

But we’re not there yet. We live in the meantime.

I say that last sentence to myself and others all the time now. We live in the meantime. Or the “not yet.” We are homesick for a home we have not yet lived in.

There are sentences like this all through the book, words and images that will make you stop and savor them, try to engrave them on your heart. I see it’s available as an audiobook. I’m sure hearing those gems would be lovely, too. It’s easy to read. I don’t want to say it’s lighthearted but it’s not heavy or textbook-like in any remote way. I think you could call it a conversational tone. I encourage you to read this book.

The book is organized with chapters named by the phrases and words of the prayer of Compline.

This book had so many “gems” on the pages—sentences that really struck me and seemed to almost glow—my copy is full of underlining, arrows, notes, and dog-eared corners.