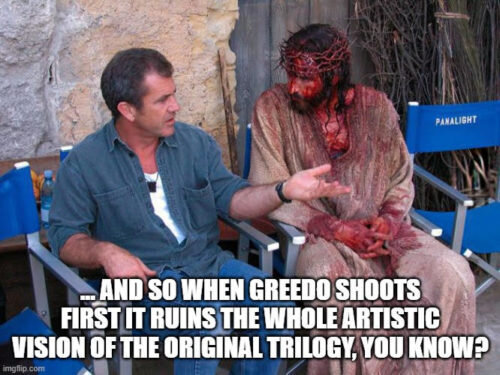

Comparative suffering - Mel Gibson and Jesus

I saw the meme referred to here before, and this discussion of Zadie Smith's writing about it on the Mockingcast was great. I wrote along these lines myself in my last email of God's love.

Love, Compassion, and the Relative Suffering of Christ on the Cross: Intimations by Zadie Smith

by CJ GREEN on Aug 5, 2020

Zadie Smith’s Intimations is a short collection of essays about life in corona-time. Most of them are fixed on that singularly bizarre March/April when “surreal” was the only word most of us could cough up; not surprisingly, Smith has a more expressive vocabulary. If the book arouses any suspicion, it’s that it came too fast, but personally, I appreciate the hasty documentation. It’s like reading a bundle of letters from a friend. And I wanted to share a few snippets.

In an essay called “Something to Do,” Smith reflects on her new schedule in lockdown: “in the first week I found out how much my old life was about hiding from life.” She concludes that capital-L Love—“not something to do, but something to be experienced, and to go through”—is what makes life worth living. Not work. Not even art. Of her life pre-corona, she writes:

Conceiving self-implemented schedules: teaching day, reading day, writing day, repeat. What a dry, sad, small idea of a life. And how exposed it looks, now that the people I love are in the same room to witness the way I do time. The way I’ve done it all my life.

The book’s final section is comprised of pithy acknowledgments, “Intimations.” Here Smith quotes Lorraine Hansberry, playwright and author of A Raisin in the Sun:

“When you start measuring somebody, measure him right, child, measure him right.” Therefore: compassion.

To see a person fully is to feel for them. It’s this full, empathetic view that makes Smith such a good novelist and assessor of our current predicament.

Along similar lines, in “Suffering Like Mel Gibson,” Smith addresses the increasingly modern tendency to compare suffering: to neglect one’s pain by measuring it against someone else’s. A long paragraph, it’s nonetheless worth mulling over. Mostly because she evokes Christ on the cross, who, despite everything, had faith that death was not the end.

… I was sent a meme that made me laugh out loud: a photograph of Mel Gibson, in a director’s chair, calmly talking to Jesus Christ himself. Jesus (also in a director’s chair) was patiently listening while soaked from head to toe in blood and wearing his crown of thorns. The caption read: “Explaining to my friends with kids under six what it’s been like isolating alone.” As a rule of social etiquette, when confronted with a pixelated screen of a dozen people, all of them inquiring, somewhat half-heartedly, as to “how you are,” it is appropriate to make the expected, decent and accurate claim that you are fine and privileged, lucky compared to so many others, inconvenienced, yes, melancholy often, but not suffering. Mel Gibson but not Christ. Even Christ, twenty feet in the air and bleeding all over himself, no doubt looked about him and wondered whether his agonies, when all was said and done, were relatively speaking in fact better than those of the thieves and beggars to his left and right whose sufferings long predated their present crucifixions and who had no hope (unlike Christ) of an improved post-cross situation … But when the bad day in your week finally arrives—and it comes to all—by which I mean, that particular moment when your sufferings, as puny as they may be in the wider scheme of things, direct themselves absolutely and only to you, as if precisely designed to destroy you and only you, at that point it might be worth allowing yourself the admission of the reality of suffering, if not for yourself, exactly, then in preparation for that next painful bout of videoconferencing, so that you don’t roll your eyes or laugh or puke while listening to what some other person seems to think is pain.